Often Unseen, Structural Engineering Plays Critical Role

September 23, 2024

Stagehands are the people in theater who do the heavy lifting, literally. In the dark between scenes, stagehands move the set pieces around and make sure the actors get their costumes changed. They work quickly and efficiently and most of the time you don’t really see what they’re doing. However, if they don’t do their job well, Dorothy never makes it to Oz and Alexander Hamilton never becomes a Founding Father. It is the work done in the background that allows the audience to immerse itself in the world of the story unfolding in front of them.

Structural engineers are a lot like stagehands. If they do their job well, most people will never see or think about the structures they have designed. But make no mistake, the job of a structural engineer, while not flashy, is the base on which everything else is built. If the structure doesn’t hold, then all the innovative architecture or mechanical workings won’t matter.

At MKEC, our structural team works on both commercial and industrial projects with budgets from $1,000 to hundreds of thousands of dollars, and we see some interesting work on both the industrial and commercial sides.

“I think it’s been pretty eye-opening to see just the sheer number of places structural engineering is needed,” says Neil Satrom, structural engineer for MKEC. “There’s always stuff to do, and I think it’s because we’re needed in so many different kinds of projects.”

Raising the roof

One of the more interesting projects on the commercial side was replacing the deteriorating wooden roof trusses in St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in Parsons, Kansas. The church was built in 1873, and the roof trusses were original to the building. However, as the building aged, the trusses began to settle and push the walls out. MKEC was tasked with replacing the wood trusses with new steel ones without changing the aesthetics of the building.

“We came in and the goal was almost to mimic the existing wood frame structure just replacing the elements that wanted to deform with steel,” Satrom says. “So we came in, and we reused the existing truss-bearing locations, and instead of just pocketing the wood into the brick, we added steel embed plates on the walls that we anchored into the masonry. Then we could weld our steel structure down and use steel beams that could support the roof.”

One challenge was that the ceiling hung from the roof trusses, which meant shoring up the ceiling with scaffolding before removing the trusses then reattaching the ceiling to the new steel beams.

“Once we were all finished, nobody could tell that there’s steel up there unless people go climbing around in the attic,” Satrom says.

Starting from scratch

While a 140-year-old church provided an interesting challenge, new construction requires a different thought process.

We recently worked on a 250,000-square-foot VA medical clinic in Raleigh, North Carolina, which required a lot of coordination with the architect, and interdisciplinary cooperation to design and build the two-story structure.

“It was the biggest project I’ve worked on,” Satrom says. “It was really, really big. There were lots of drawing sheets, lots of planning, lots of people to work with. With a project this large, you have to provide expansion joints in the building every 200 feet or so. Which meant we split this building up into five different sections. Each section had its own set of analysis models. Once we analyzed each portion of the project individually, we would bring that information together to make sure each piece fit properly into the overall project to form one seamless building. While large projects like this can have their logistical challenges, it’s fun seeing all of the pieces come together.”

Designing with a flare

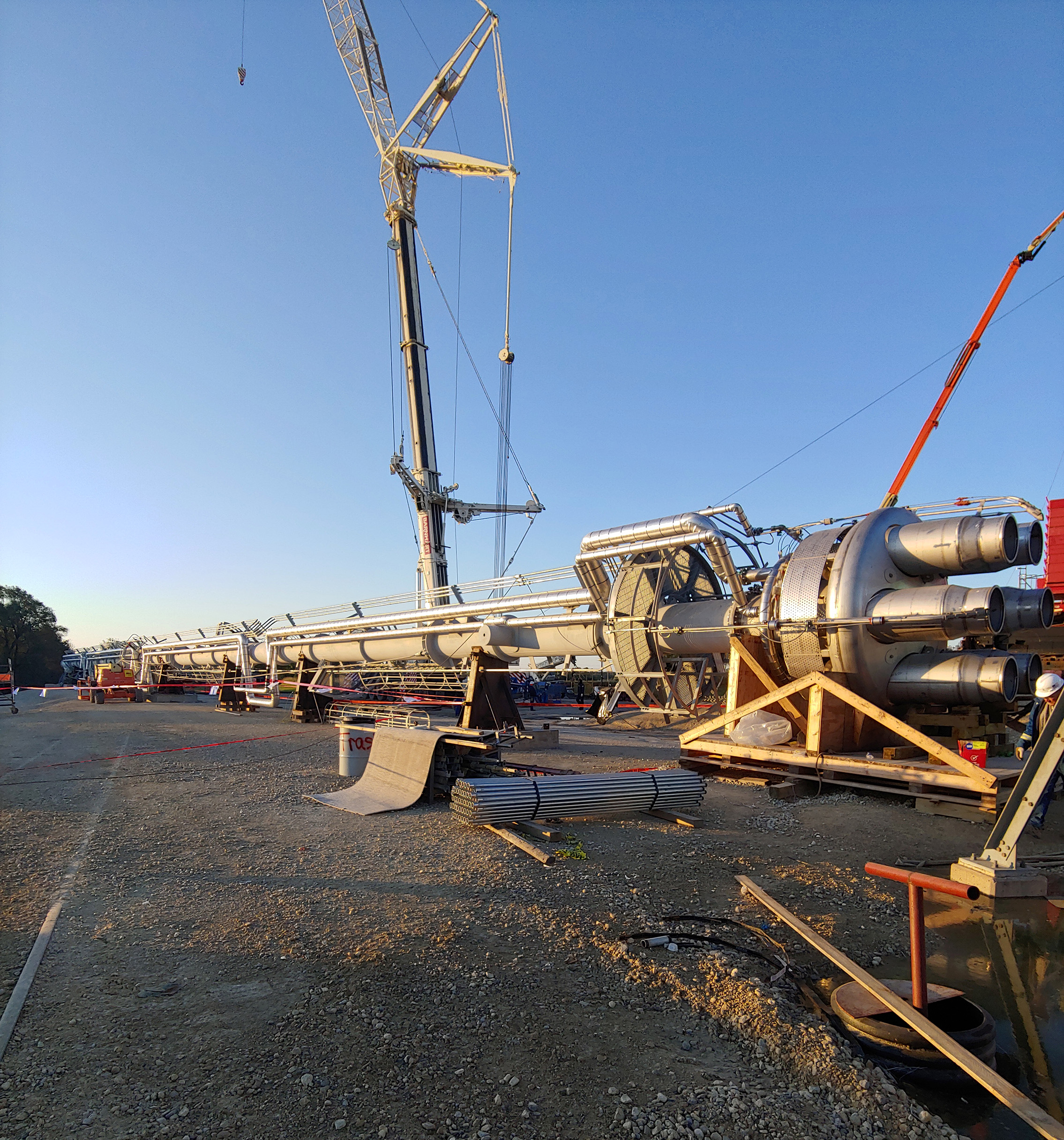

Our structural projects are no less interesting on the industrial side. A local refinery in El Dorado, Kansas, called on our structural team to replace the West Refinery Flare, which we originally thought would be a straight-up replacement job. However, as the job took shape, our structural engineers realized this would be more than just a one-for-one replacement.

“They wanted to increase the number of platforms, which adds weight,” says Andre Razo, structural engineer and principal for MKEC. “Then they wanted to change out the flare tip at the top. The original one was about the size of a trash can. They changed to this very large, 12-foot diameter one. I think it weighed like 10,000 pounds, and they wanted to put it at the top of this 300-foot-tall stick.”

Initially, we were going to lift the flare into place in two pieces, but our client decided they wanted it to be one piece and fully dressed with the platforms and flare tip already installed before lifting it into place.

“That was a fairly sleepless night when I knew they were going to take it the next day,” Razo says.

But despite a last-minute phone call and field visit to check the deflection, the flare was set in place in 2019, two years after the project began.

Expanding the rails

Recently, one of our clients asked us to design their rail expansion in Geismar, Louisiana. The rail cars would be loading and unloading renewable fuel products made from by-products and would need to utilize steam heating to liquify the products for unloading.

The space at the site is limited, so our engineers had to get creative. The project had to be built in two phases. Phase two would be built over the existing unloading rack, so a 25-spot unloading rack had to be built in phase one.

To get around the space constrictions, rail racks and other structures were prefabricated and shipped to the site.

“You could only ship components that are so long, so we had to break it up,” Razo says. “We had to work within the constraints of the train car dimensions. We created modules where we fabricated and erected all the steel and put all the piping in before it shipped. The modules were then shipped on a barge from Houston through the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway to Geismar, so we also had to take into account the motion of the water when designing the modules. Luckily, their coastal waterway is just like a really slow-moving river, so that was pretty easy.”

Whether it’s raising the roof of a more than century-old church or expanding a railyard, our structural engineers are dedicated to solving problems.

“The thing that I love about my job the most is I get to come in and figure out some fairly complex situations,” Razo says. “We’re working through a lot of situations that are very unique. You don’t see large foundations for precision equipment with very small deflection requirements, or a foundation for a heavy vessel every day. I just like all the different things we get to do here.”

“The thing that I love about my job the most is I get to come in and figure out some fairly complex situations.”

Andre Razo, Structural Engineer, Principal

And while much of their engineering may be out of sight, our structural engineers love to see the finished product.

“I just like the very tangible nature of it,” Satrom says. “I come in here and work on something, and there’s this actual physical structure you can point to. I like being able to drive around town and point to those projects that I worked on.”

“I come in here and work on something, and there’s this actual physical structure you can point to. I like being able to drive around town and point to those projects that I worked on.”

Neil Satrom, Structural Engineer